I’m continuing to read Thoreau’s Importance for Philosophy. I just finished a fascinating article by Douglas R Anderson titled “An Emerson Gone Mad: Thoreau’s American Cynicism.” Anderson views Thoreau as a philosopher continuing in the tradition of the Cynics, and sees his writings, particularly Walden, as a modern application of Cynic philosophy.

To understand this premise, it’s useful to review Cynicism. Originating in ancient Greece, Cynicism was a practice of philosophy which sought to create a lifestyle that was in accord with nature and man’s natural state (very much like Thoreau’s conception of Wildness.) The Cynics rejected conventional notions of wealth and power. They did not separate themselves from society (the way that other, similar groups do), choosing to pursue their lifestyle among everyone else. They lived in public poverty. They sought happiness through less (less commitments, less obligations, less possessions).

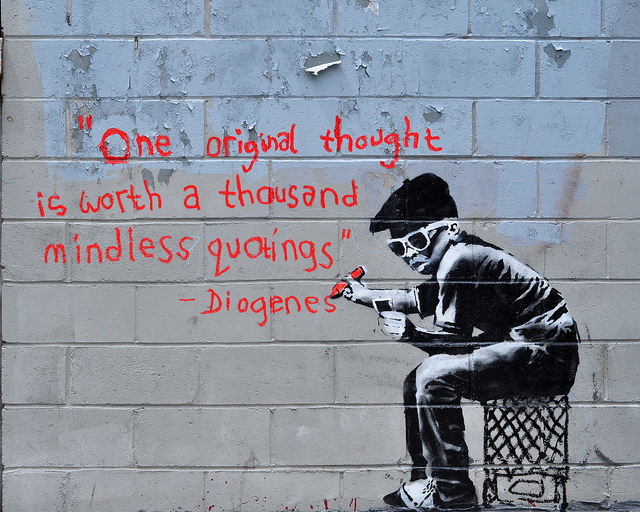

Diogenes of Sinope was the most famous Cynic. Because os extreme embrace of this lifestyle, he was kicked out of Sinope before settling in Athens. He earned the nickname Diogenes Kynikos, or Diogenes the Dog-like.

Their public rejection of, and indifference to, cultural norms was also characterized by open criticism of behaviors in others that were contrary to their ideas of good living, virtue, and freedom from desire. Emphasis on this critical view of others eventually led to our present use of ‘cynic’ to mean a person who distrusts the motives of others.

Anderson points out three modes of freedom central to Cynicism: eleutheria (freedom from interference by others), autarkeia (self sufficiency), and parrhesia (freedom to speak directly and bluntly). These must work together to create “the possibility of a thoughtful life.” Anderson believes that achieving these three freedoms was Thoreau’s “chief aim.”

Thoreau’s experiment at Walden Pond was an effort to achieve these freedoms. Eleuthereia was pursued both through solitude and poverty. Together these allowed him to free himself from the conventions and laws of society, which can inhibit freedom. Solitude separated him from society for a time, allowing for self reflection and a deeper understanding of his natural self. During his time at Walden Pond Thoreau frequently went into the village and visited friends. His solitude was not absolute as he continued to interact with society, which is an important feature of Cynicism.

Poverty gave him freedom from the constraints of possessions and the cultural competition to acquire and own. It is important to note that his poverty was chosen, and vastly different from the pervasive and problematic poverty caused by lack of means. He had everything he needed, which was little. He was not controlled by his possessions. For Thoreau “a man is rich in proportion to the number of things he can afford to leave alone.”

As an example of Thoreau’s pursuit of autarkeia, self sufficiency, Anderson points to his attitude about the body—that we should “strengthen and beautify, and industriously mould our bodies to be fit companions of the soul.” We can see evidence of this in Thoreau’s simplified diet and his lifestyle (growing his own beans, chopping his own wood, walking). Taking care of one’s body is important to achieving autarkeia.

The combination of self sufficiency with freedom from interference by people and societal conventions allows for the third freedom: parrhesia, freedom to speak directly and authentically. This is more than just freedom of speech. Anderson says, it must be “driven by living through obedience to the laws of one’s own nature.” Thoreau’s writings are a clear example of his parrhesia. In them he sought to bring his readers “to an encounter with their own living conditions.” Anderson continues:

Poetry, experience, irony, sarcasm and humor (light and dark) become Thoreau’s philosophical tools; they are more penetrating, more provocative, and ultimately more effective than the tools of math and logic employed by the heavy-handed moderns and, in our time, by mainstream Anglo-American thought. The American Cynic philosopher is thus engaged in learning how to live well in achieving a radical form of freedom that involves provoking others to consider the possibility of their own freedom.

The rest of Anderson’s essay explores the relationship of Cynicism to Thoreau more fully, looking to re-frame certain conceptions that exist about Thoreau—he was a hermit, he was an anarchist. I think it’s very much worth finding and reading if you’re at all interested in Thoreau.